Tea Processing is a bit like my library’s spiritual successor to Tea Growing. It’s not the ACTUAL successor, he wrote another book called Tea Manufacture that this book actually references (among others). But that book’s in my public library’s Collection, so I haven’t gotten around to checking it out because it requires getting a librarian to pull it out of the bulk storage… They just don’t trust you with access to the high density shelving. Well, there’s enough kids running around who’d think it’d be funny to try and close the shelves on someone, I suppose.

I went down to my own university library’s high density storage, though. It’s a separate collection within the library meant for graduate student research; it’s got its own HD 9198 section, so every book I thought we had but couldn’t find. Another hidden store of tea information. That’s just one section. I wish my library let you search specifically by collection, but unfortunately it doesn’t. So I don’t know what all is down there.

At any rate, this is another book that isn’t readily available for purchase. It’s rarer than Harler’s handbooks even, since I don’t think this is really a regular publish; it’s part of the FAO Agricultural Service Bulletin. Issue 26, if you can find it. It’s very informative, though, and it’s the kind of book I would (along with Harler’s handbooks) recommend to those few tea-heads I know who are trying to grow their own potted tea bushes.

I don’t know what much I can say as a review, since it’s not widely available. If you can get your hands on it though, I’d recommend it. It really makes you stop and think about all the small-time farmers out there, and all the tea-heads that have gone so far as to go out and buy tea saplings or seeds. There’s so much work and science that goes into processing it actually makes me wonder if the Cowichan Valley’s tea farm is prepared. Also, what’s up over there. Haven’t heard much in a while.

The book divides orthodox production from unorthodox production (which is put under the header of Modern Tea Processing); it details the chemicals in fresh and made tea and how they change through each step in production, and makes a point of explaining what part of production affects what quality (aroma, flavour, briskness, strength, colour…). It has to cover a lot of ground, but manages to still include a lot of detail.

Because the book uses C.R. Harler’s handbooks as a reference (among others), there’ll probably be a lot of overlap once I manage to get my hands on a copy of Tea Manufacture. It also picks up where Tea Growing left off, how genetics of tea affect the different qualities, and how the different varieties are treated. Specifically how growing height and production affects each varietal, and how to maximize qualities from each. It explores how high-grown teas change versus low-grown, and how they’re further affected by the altitude of the production factory itself.

In order, it deals with withering, rolling (leaf distortion) and drying (firing), as well as the current (for the ’70s) machinery and techniques being used. There is a tone of lament in Werkhoven’s voice as he describes how unorthodox (“modern tea production”) techniques are slowly becoming the norm, as tea colour and strength become favoured over quality, flavour and briskness. Still, he does a dutiful job describing the process, and covers all machines used for each step in the process as of 1974 (as well as a quick rundown on the history of machines–year and country of invention).

Because the book covers so much, it would take a number of read-throughs before I’d consider myself well-versed on it. Such topics as, ‘what are the wet and dry bulb temperatures required for low-grown Indian factories’ dryers in order to avoid stewing and case-hardening?’ And ‘in combination CTC/Rotorvane production, how many times is a batch put through the CTC machine, and in what order are the two processes done’ plus ‘to which degree of withering should the tea be before Rotorvane distortion, if at all’. ‘When is a second firing desired’. ‘At what level of the dryer does case-hardening occur’. it’s a lot (these would be good exam questions, though). Though a lot of the numbers allude me, I remember (because of how often it’s repeated), ‘final tea should be fired to within 3% moisture’. Delivered tea often has as much as 6% moisture content before it becomes detrimental.

There’s quite a bit of extra information in the appendices, such as a glossary; I originally intended to scan them and offer a pdf, however after realizing the glossary alone is about thirty pages, I think I’ll put that off for a bit. But it’s a damn good book, I’d definitely recommend it, and I think I learned a lot.

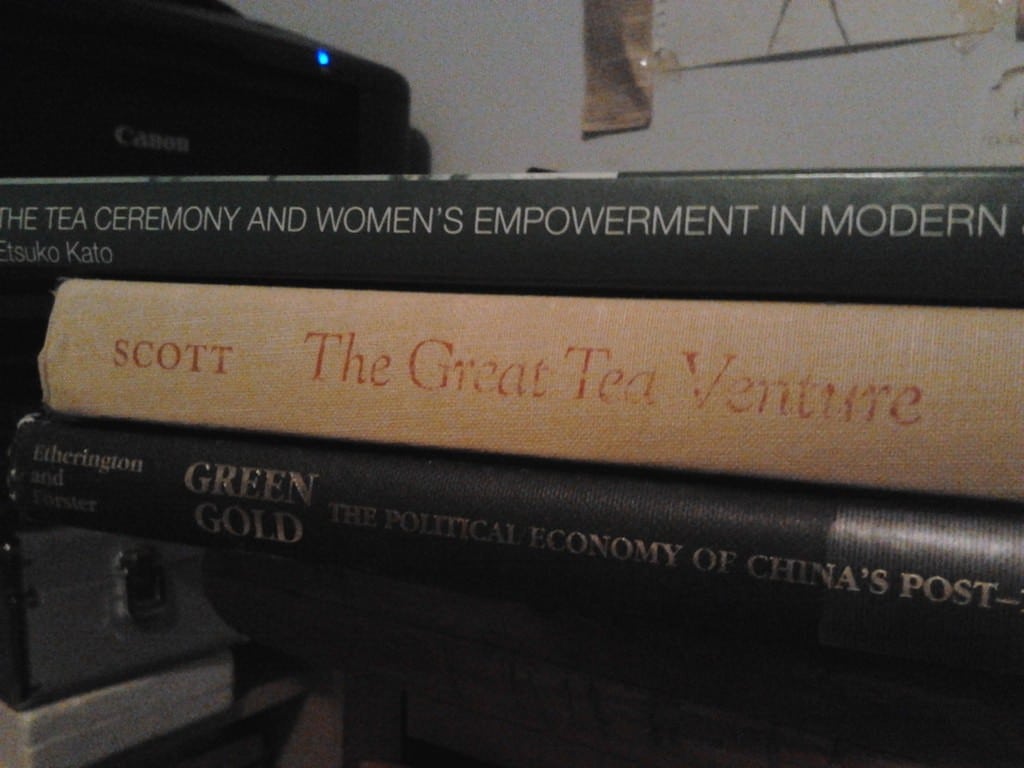

Next on the list of books to read, from my library-check-out stack:

- Availability: Not very. Worldcat has entries which along with local zip codes might help in locating any local libraries with it (as with most online book databases, there are several entries for the same thing)

- Catalogue Card from FAO’s online database for reference

- OpenLibrary does not currently have a copy

- Table of Contents

01/08/2015 at 5:24 AM

It is always nice to have access to the content of “old” books on tea, tea industry and tea processing.

27/01/2016 at 4:48 AM

Thank you for introducing this book. Would you please let me know which library you borrowed it? If I know, probably I can borrow via Inter Library Loan. Please let me know about the book, “Tea Growing”.

Thank you,

Jongbok

28/01/2016 at 7:39 PM

I tend to avoid giving out my location. However, I would suggest checking worldcat.org:

https://www.worldcat.org/title/tea-growing/oclc/3238220&referer=brief_results

If you input your location, it will give you the closest libraries to you that have a copy of the book, for you to either visit yourself or request an interlibrary loan from.