I’ll usually swing back around to this blog with a pretty dire opinion of my activity, but if I can manage four posts a year (in both 2021 and 2020!), then I’m pretty happy with myself. (Even if I did read months back)

I’ll usually swing back around to this blog with a pretty dire opinion of my activity, but if I can manage four posts a year (in both 2021 and 2020!), then I’m pretty happy with myself. (Even if I did read months back)

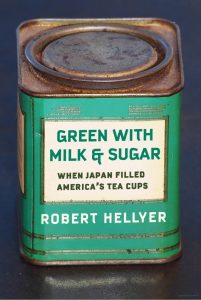

Of the 2021 releases I talked about previously, this’ the only one I’ve gotten around to reading so far. This was the book I was most interested in (so the only one I put on pre-order–it was my birthday present to myself, but with turbulent pandemic delays, it didn’t actually get to me until the end of November), and I don’t think there’s really any other books out there that cover this specific topic to this extent and dedication.

Green with Milk & Sugar is about the growth and decline of Japanese tea in America, interweaving the cultural climates of America, Britain, China and Japan from the 1800s all the way up to the 1940s. It follows how these relationships and ideals shaped America’s tea tastes over the years, made them distinct from Britain’s, and how those tastes eventually declined during the twilight years of WWII.

Hellyer frames this story around his family’s involvement in the industry, as Japanese Tea Importers to the US during the turn of the century. It’s a personal connection on top of his own CV as a history professor of modern Japan, and from a story-telling perspective, a useful anchor. He doesn’t focus on Hellyer and Co specifically, instead dropping them into the larger picture as an insight on how global events were effecting individual companies at the time. I think it’s a useful tool that grounds the narrative.

I found Hellyer’s writing and presentation straightforward and easy to read. Japan’s large presence in America during the early 1900s is something that has popped up in statistics across several books I’ve read, but not touched on as most works were Britain-centric.

The book opens with a brief history of how tea evolved in Japan, and Japan’s relationship with China at the time, before moving into America’s relationship with tea in the 1700s. Flowing into the 1800s, we see the rise of new tea-producing countries through the Dutch and English East India Tea Companies, reshaping the landscape (literally, figuratively). America initially shares very similar tastes with the British, but as the British sought to cut out any tea not produced under the Crown, these tastes diverged; as other tea-producing countries lost Britain as a customer, those countries looked to America to fill the gap.

Racism, further fueled by the rise of the ‘clean food’ movement during the Victorian Era, played similar roles in both America and Britain. Britain’s tea tastes, once equally preferring of green and black teas, slowly swung towards Indian blacks. This decline in green tea consumption was not mirrored in America, who became one of the main importers of green tea at the turn of the century. Instead that shift was from China-sourced teas to Japan, as the latter pushed themselves as the ‘cleaner’, more transparent choice, free of ‘colourants’. Chinese tea was shamed as ‘unclean’ and insidious, full of fillers and who-knows-what, with caricatures of Chinese men working tea leaves in unclean conditions. It acted on racisms already at play at the time, and it worked up until WWII when perception of the Japanese shifted drastically in the US.

This is really the only major book that focuses on this topic to this extent, and I highly recommend it as a good addition to anyone’s tea library. Also solidly affordable, compared to some of the other books I’ve been eyeing lately.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.